When travelling in the south we’ve visited many Civil War sites: battlefields, forts, headquarters buildings, cemeteries and the like. A couple of years ago we even visited the Union prison camp on Delaware Island in the bay at the mouth of the Delaware River. That visit did nothing to prepare us for Andersonville.

If you are familiar with the book and movie about Andersonville, you may have an idea about what a horrible place it was. But I’ll start the story of our visit at the beginning.

When arriving at the Andersonville National Historic Site in Georgia we were surprised to learn that the National POW Museum is located here, in a very rural, out-of-the-way part of Georgia. The message of the museum is one that should be on display in Washington, DC, but it’s here where relatively few citizens, and probably even a smaller percentage of politicians, can see it.

Georgia we were surprised to learn that the National POW Museum is located here, in a very rural, out-of-the-way part of Georgia. The message of the museum is one that should be on display in Washington, DC, but it’s here where relatively few citizens, and probably even a smaller percentage of politicians, can see it.

The first thing I saw in the museum was this poster which lists the daily count of prisoners, and deaths that occurred on this date 150 years ago when the prison camp was in operation. In case you can’t read it, the poster says there were more than 32,000 Union prisoners there, 81 deaths, and more than 5500 burials since February. More on the prison camp later.

The bulk of the museum exhibits relate to the history of war and the taking of prisoners of war. The Geneva Convention regarding the treatment of POWs, and the controversies related to both the behaviors of the captured soldiers and those of the captors are discussed in detail.

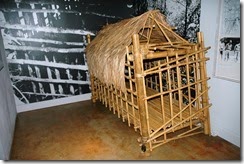

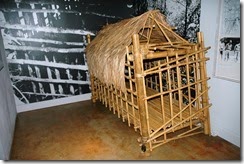

This is a reproduction of the type of cage many US warriors were kept in by the North Vietnamese. There are also many multimedia exhibits utilizing letters written home by POWs read by actors. It is a terrific, powerful museum, and my only question is “why is it buried in the middle of rural Georgia when it should be seen by so many more people than will ever visit this small town.” The simple answer is the obvious one: Andersonville was the worst prisoner of war camp on American soil, so the location does make sense in that regard. But more people should see this museum.

The National Park Service provides a loaned CD at no cost to guide visitors on a driving tour of the Site.

When we first arrived at the site of the prison camp our first thought was “I guess the NPS decided not to reconstruct any of the buildings that were here.” The post in the foreground of this image depicts the location of the stockade boundary wall and the white post in the background shows the location of the “deadline”. If a prisoner crossed this line, he was shot.

Several sections of the boundary wall have been reconstructed. But again, where are the buildings? There were as many as 32,000 prisoners kept here – where did they live?

There were no buildings for the prisoners because they were moved here before the facility was completed. They lived in the open in makeshift huts called “shebangs” which were put together with blankets, scraps of wood and anything else the prisoners could find.

Food was scarce, and for most of the 14 months the camp operated the only water available was from this tiny stream known as the Stockade Branch. The stream quickly became polluted with waste from a bakery that was providing inadequate food as well as human waste. This was the only source of water for as many as 32,000 men crammed into a 16 acre stockade with virtually no shelter. The stockade was designed to hold 10,000 prisoners, and the horrible conditions, lack of clean water and very little food resulted in the death of 13,000 Union prisoners during the 14 months in 1863 and 1864 that the prison camp was in operation.

Which brings us to the next part of the Andersonville National Historic Site: Andersonville National Cemetery.

When prisoners died they were buried in this cemetery under numbered wooden grave markers. A union prisoner kept track of the names associated with each of the numbered graves, and after the war Clara Barton led an effort to provide permanent marble grave markers for each of the fallen soldiers.

It’s important to remember that these soldiers died, not as a result of battle, but as a result of the inhumane and inhuman conditions in the prison camp.

The cemetery has been in continuous use as a National Cemetery since the end of the Civil War and the graves of veterans of all US wars can be found there.

This sculpture is the Georgia Monument at one entrance to the cemetery. It is a moving depiction of prisoners of all wars and shows both the suffering and the dependence one prisoner has for his or her fellows in order to survive.

By the way, the Confederate officer in charge of the stockade at the time the war ended was tried for war crimes, convicted and was hanged in Washington. At his trial his defense was basically: “I was just following orders.”